The Philippine Star,

Monday, April 30, 2001

On April 6, Friday, before the Holy Week, the Ayala Museum on Makati Ave., Makati City, inaugurated ‘The Art of the Cross’, an art exhibit featuring crosses. The show will go on until June 30, roughly coinciding with the traditional Christian season of Eastertide.

For the folks who reach a spiritual high from the Visitas Iglesias they made during the Semana Santa, this is the fix that will keep them up there. And, of course, if you are a cultural buff in search of rare, centuries-old items, or simply, pieces of scholarly interest, then ‘The Art of the Cross’is a must-see for you.

Unfortunately, the museum was closed during the Holy Week, so the show opened to the public again only on Tuesday , April 17, the museum’s first working day after the holidays.

To complement the exhibit, the Ayala Museum has also prepared a set of lectures given by the country’s top authorities in the Spanish colonial cultural field.

The first of these, appropriately, was “Weave!”, delivered by Elmer Nocheseda on the morning of April 6.

Nocheseda is the guy who can tell you all about the many styles and techniques of weaving the palaspas, the crosses fashioned of young palm fronds blessed by the priests on Domingo de Ramos (Palm Sunday).

On the afternoon of April 6, ‘Holy Week, Filipino Style’ was the topic of Ateneo social scientist Dr. Fernando N. Zialcita.

The other parts of the lecture series are: ‘Subli: Laro at Panata’ given by U.P.professor of music history, Dr. Elena Rivera-Mirano, last April 28, 3-5 p.m.; ‘Viva Santa Cruz’, to be given by the highly respected Dr. Nicanor G. Tiongson on May 5, also 3-5 p.m. On May 12, also 3-5 p.m.,jewelry expert Ramon Villegas will talk about ‘Heirloom Crosses’.

An exhibit on crosses is certainly something that does not need so much justification in this country which is predominantly Christian.

And even if the depiction of images of Christ, Mary and the saints may be a practice exclusive to Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christians, the custom is not altogether so strange as to shock or offend those who are not in favor of it.

In the name of art and culture, we have accepted the relevance of Buddhist and Hindu images have to our Chinese and Indian friends.

We have also been so used to almost daily allusions to, or representations of, Venus, Adonis, Hercules and other members of the Greco-Roman pantheon such that we have hardly seriously thought of these personages as deities revered in pagan Greek and Roman times as fervently as we do our God and Christian spiritual beings.

Filipinos in general have never had any difficulty in accepting the Roman Catholic culture of iconism, perhaps because image-making was a custom rooted in pre-Hispanic Philippine life.

The cross motif has also been present in the country even before the Spanish coming. Crosses formed part of the repertory of designs incised on excavated pre-Hispanic earthenware. The textile specialist Sandra Castro points out that many ethnic groups in the Philippines like the Mandayas, Mangyans and Bilaans, have also utilized cross motifs in their traditional weaves.

‘The Art of the Cross’ is focused on the corss as a motif in Philippine Christian art particularly as a result of the Spanish presence for more than 300 years in the country.

Sourced from private collections, as well as from the museum’s own, the examples in the show range from small types, like pieces worn bodily as jewelry accessories to life-size or relatively big ones used as focal images in both church and home altars.

The small ones were mostly worn hanging from the neck or pinned to the shirt or blouse to function as amulets or protection against evil and misfortune.

Objects using the cross design or motif, of course, evolved into precious pieces of jewelry, as they became fashioned out of gold or silver and encrusted with expensive stones like diamonds, rubies and pearls.

Many places in the Philippines became the hub of jewelry-making during the colonial days as the demand grew for for elegant bodily adornments specially crosses.

Among these places are: Laoag, Ilocos Norte; Vigan, Ilocos Sur; Meycauayan, Bulacan; and the districts of Santa Cruz and Quiapo in Manila. These centers even developed processes and techniques as well as styles and designs uniquely their own.

An example of an indigenous ornamental design is the sinan-siit exclusive to Ilocos and Cagayan smiths. As the Ilocano term implies, the motif resembles tinythorns (tinik in tagalong) soldered to jut out from the body of the cross usually of chiselled openwork.

It may have been inspired by the crown of thorns worn by Christ during his Passion, an object which artists and artisans have depicted as something fashioned from a variety of prickly cacti like those growing in the arid Ilocos terrain.

The cross as a common shape is a simple intersection of two lines. In Christian art and religion, however, it is an artistic rendering of an upright post with a traverse beam, the contraption to which condemned persons in ancient times were transfixed (tied with ropes or nailed) as a form of capital punishment.

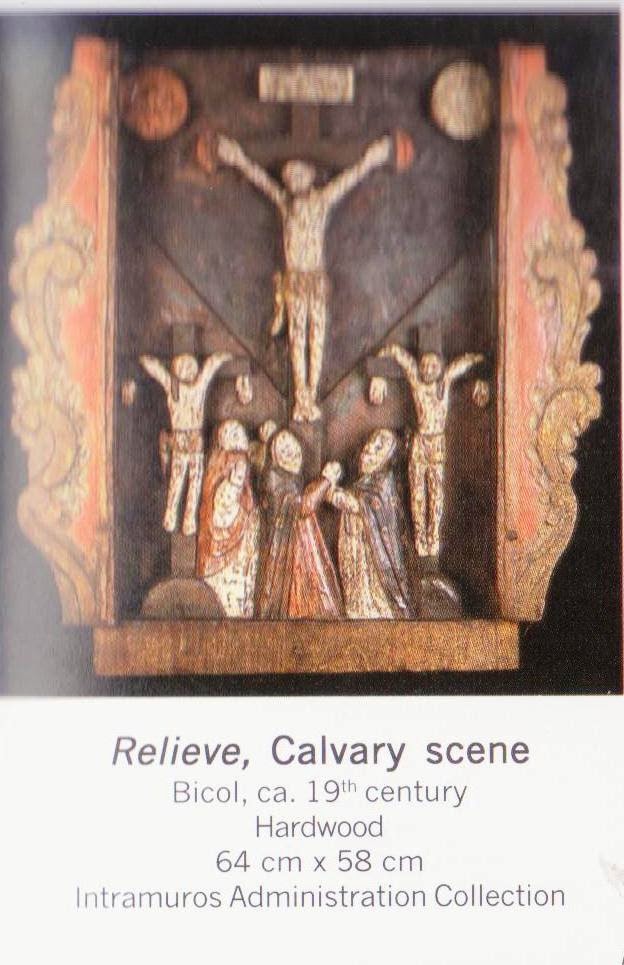

It is the central symbol of the Christian faith, crucifixion being Christ’s humiliating manner of death through which he redeemed the world from eternal damnation. Crucifix is the word we use for the object that includes the corpus or body of Christ hanging on the cross. Crucifixion refers to the punishment and a Crucifixion scene of Christ iften does not depict him alone but the entire Mt. Calvary scene.

The Ayala Museum exhibit affords us with a rich experience of the Philippine Christian or more specifically. Local Roman Catholic interpretation of the crucifixion of Christ.

Like any of the subjects of Christian image-making before realistic portraiture and photography were developed, all these representations were just products of the artistic imagination.

No object from the time of Christ is still in existence to tell us how he or his mother and his disciples looked like. As a reflection of the human imagination, the Philippine interpretations of these Christian themes, illustrate how we have accepted and imagined the Christian experience.

Across Philippine art history, these images vary depending on the mental and/ or spiritual intelligence of their makers, their skills as artists and the materials they used to express this. As products of a continuum, these objects requires an understanding of the same factors in order for us to fully appreciate their artistry or their relevance to that particular point in time (what century? what region? who was the specific artist?) in which they were made.

The show features about 30 objects inviting us to ask questions ranging from the practical to those specifically dealing with art historical issues and interests. How were these made?

And indeed, we marvel at the complexity and intricacy of workmanship of some, like the metal and ivory pieces. Who made them? Why didn’t the carvers and smiths who made them sign them just like the one-of-a-kind religious sculptures we see nowadays. What are the sources and influences of their styles? My favorites in the exhibits belong to two types.

One is the crucifixion scene in slim liquor bottles. For one, the bottles themselves are antiquities since this is a genre that flourished in the early part of the 20th century. The greenish bottles are particularly pleasant to the eyes

This genre traces its beginnings to Victorian glass globe table pieces containing flowers and elaborate multi-figure scenes. The bottled crucifixion scene is a form of prison art. (Today, prisoners still make bottled art but their subjects are mainly galleons and rural scenes).

I used to be puzzled about how the entire crucifixion tableau could be inserted inside a bottle with a mouth so small until someone pointed out to me that all the materials were placed inside via an opening at the bottom of the bottle which was later on soldered again.

This tableau often consists of a Christ on the cross, Mary and Magdalen or John (and sometimes there are the three crosses of Mt. Calvary) plus an appropriate setting of mountains and trees. For realism, the face and limbs of the figures may be made of polychromed wood, while other parts make use of materials that imitate the textures and colors needed.

The second type that I like is the classical crucifixions, whether carved of ivory or wood. This is a form of urban art giving us an idea of how master carvers in Manila, Paete, Laguna and Vigan or San Vicente, Ilocos Sur, interpreted Christ on the cross as inspired by Renaissance and Baroque prototypes.

Many examples from the 16th to the early 20th centuries, have been preserved. We know that the Chinese-looking Christs date to the earliest period of the colonization. By Chinese-looking, we mean slit eyes, small nose, small thin lips and lanky limbs. The more sinitic, the earlier.

Christ’s features become more and more Caucasian and also more and more formal in approach as the carvers also change in their training, that is, from apprenticing in the talleres or workshops to professional tutorship under the Academia de Bellas Artes.

Pre-20th century cult or devotional objects in the Philippines were seldom signed. These pieces were generally not regarded as art despite their evidently high artistic quality. The awareness of human participation in the creation of a saintly image would certainly distract devotees in the performance of their devotional activities.

In this crucifix, Christs’s body is made of tinted wood and his features are painted with realistic reasons. He is equipped with hair made of curled fiber, a crown of thorns of beaten metal and an elaborately tooled loin cloth.The author is unknown.

I have encountered several examples of this style, apparently done by one person, but unfortunately, the pieces could never be traced to their maker or his descendants who could inform us who he was. I am inclined to believe that his environment dictated this situation of anonymity. The artist belonged to that period in which his work was not considered as a work of art but simply an object of devotion.

The second example is a classical ivory piece identified as by Leoncio Asuncion (1813-1888). Leoncio belongs to the famed artistic Asuncion clan that produced the exquisite portraitist Justiniano and the religious painter mariano. The attribution to Leoncio is correct because the piece came from the artist’s descendants who donated it to the Ayala Museum. In this case, we witness a situation of vigorous artistic awareness.

Asuncion’s Christ is very Caucasian in features and when placed beside the anonymous piece mentioned above, its realism appears to lack force and dramatic intensity.

The third example was done in 1890. Its merits lie specially in the fact that it is so far the only known surviving work of the acclaimed sculptor, Marcelo Nepomuceno (1871-1922).

Marcelo’s work definitely lacks the realism of the anonymous as well as the Leoncio Asuncion piece. The piece also takes on a more secular tone and shifts to Magdalen’s lament.

The artist’s focusing on the repentant Magdalen and not on the mystery and drama of the redemption presages the wordliness and materialism of our times.

All photos from "Art of the Cross: A Philippine Tradition", by Sandra B. Castro. Catalog Exhibit, Ayala Museum. 2001.

No comments:

Post a Comment